Carmarthenshire Bogs Project

Page updated on: 31/08/2023

Formed over thousands of years, lowland bogs are increasingly rare examples of an important peatland habitat that support specialised and often threatened wildlife. They are amazing habitats. You may well be familiar with images of the vast blanket bogs in upland areas of Britain and Ireland but you may be surprised to learn that within Carmarthenshire we have some important lowland bogs, which have developed within our landscape over thousands of years. Today they survivors of an ancient landscape now dominated by agriculture and forestry.

In 2015 a partnership led by Carmarthenshire County Council received a grant of £43,000 from the Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF) to explore some of these bog habitats in the county. The project focused on five areas of lowland bog on areas of common land near Brechfa and Llanfynydd. The Partnership is made up of Carmarthenshire County Council, Swansea University, Dyfed Archaeological Trust and National Botanic Garden of Wales.

During the long period of their formation bog habitats have slowly grown and have kept a hidden history of their development and the changes in the landscape around them over thousands of years. For one site, Pyllau Cochion near Horeb, Swansea University studied preserved pollen and plant remains taken from a 6-m deep peat core, from a bog that started forming after the last Ice Age.

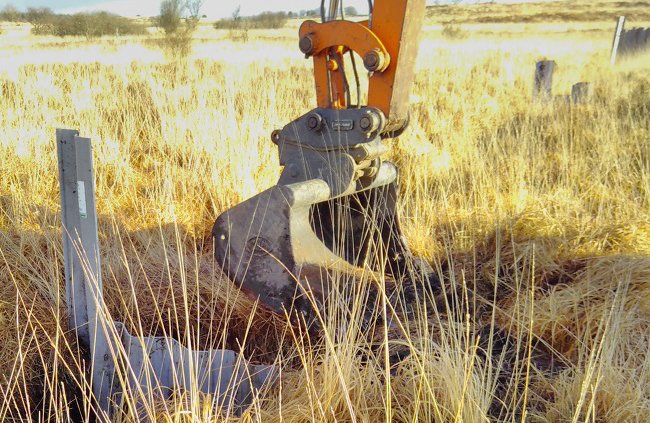

Practical action has been taken to help conserve these important habitats for the future - firebreaks were cut, a ditch blocked, fly tipping removed and Japanese knotweed treated – helping make the sites more suitable for grazing and protecting them from arson.

Dyfed Archaeological Trust worked with local schools on visits to Mynydd Bach common where, as well as learning about bog habitats, they explored a group of Bronze Age round barrows and found out more about the prehistoric landscape and the people who lived there.

Local people came along to Pyllau Cochion and explored the bogs with Swansea University to find out more about the importance of these habitats and to learn how staff and students have unlocked its secrets though analysis of a peat core from the site.

This web pages explains why bogs are so important and presents some of the exciting findings from the project – you may never look at a bog in the same way again!

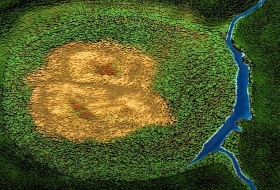

Lowland raised bogs have formed since the last Ice Age (which ended approximately 10,000 years ago) in shallow basins that have poor drainage (often with a clay base). They are fed only by rain water, which is slightly acidic and has almost no nutrients. Plant decay is very slow in these waterlogged, acidic, anaerobic (without air or oxygen) conditions. Over thousands of years the partially rotted plants, mainly sphagnum mosses, develop into peat (at about 0.5–1 mm a year) and build up into a dome that can be higher than the surrounding land – hence the name ‘raised’.

Peat bogs occupy 3% of the Earth’s surface and 70% are found in the Northern Hemisphere, of which 10–15% are located in Britain. Lowland bogs are the focus of the Carmarthenshire bogs project and there are only 800 Ha of them in Wales.

Today, in Carmarthenshire, our peat bogs are much diminished in area and condition. Over the years many have been drained or covered in forestry and the remaining sites are isolated by surrounding agricultural land.

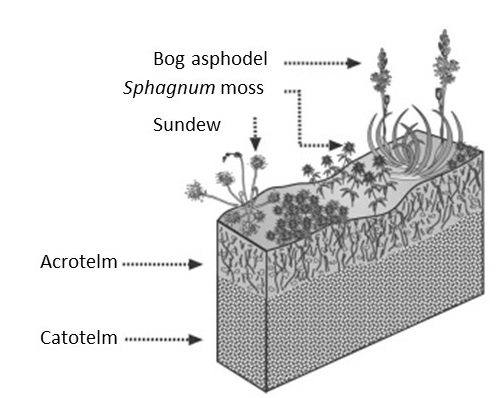

A peat bog has a unique two-layer system. The acrotelm is the top, active layer, above the water table. This is where plants decay. Underneath is the catotelm is situated below the water table and is permanently water-logged, preventing any further plant decomposition. This is how peat grows. The position of the water table shifts from season to season and year to year and directly controls the rate of peat growth. For example, during a wet year more peat will accumulate than during a dry year.

Did you know?

- In favourable conditions peat develops at a rate of approximately 0.5–1 mm per year so it would take at least 1000 years to grow 1m.

- Healthy peat bogs consist of about 95% water (by weight), the rest is made up of bog plants especially sphagnum moss.

- Bogs are one of the few ancient landscapes that still look almost exactly the same as they did thousands of years ago. They are a link to our past.

- Agriculture and forestry have damaged large areas of peatland. Commercial peat extraction to supply gardeners and nursery growers is a major threat in some areas. Gardeners have not always used peat - its use on a large scale started only in the late 1950s. Peatland wildlife depends on peat but gardeners don’t!

- Peatlands cover less than 3% of the land surface of Earth in total, but are thought to contain twice as much carbon as the world's forests. Bogs are Nature's most efficient carbon sinks. Maintaining and conserving peatland in Wales is a Welsh Government priority.

Many people think of bogs as wilderness areas with little to see, but a closer inspection will reveal some remarkable plants, insects and animals.

Peat-forming species are wetland species. Areas of sponge-like Sphagnum mosses are vital for bogs to develop and these can display a vibrant mix of colours ranging from pink, red, orange to and green. The moss plants grow close together to produce a soft spongy carpet. Microscopic plants and animals live in the water around the moss plants and these, in turn, are food for insects and spiders, which sustain frogs, reptiles and birds!

A number of plants have adapted to cope with living on a bogs and can be seen throughout the year, dotted throughout the Sphagnum mosses and drier areas. You will see the pink flowers of heathers, the ruby-reds of the cranberry, the bright yellow flowers of bog asphodel and the fluffy white heads of the cotton grass. Purple moor grass, bilberry and deer grass can also flourish.

Sundew, an insectivorous plant, has hair-like tendrils tipped with glistening, sticky, droplets that attract passing insects. When the sundew's tendrils detect the presence of prey, it traps the insect, eventually digesting the insect and the nutrients absorbed by the plant. The acidic bog habitat doesn’t provide the plant with enough nutrients, so it has evolved this carnivorous way of life.

Bird watchers may see some of Carmarthenshire’s scarcer birds with snipe, golden plover, curlew, hen harrier and great grey shrike all being recorded on our bogs.

- The bog environment is quite acidic, the plants that grow there have to be able to cope with conditions of very low fertility. Bogs can be home to a fascinating mix of specialist and rare plants and animals – see next section.

- Welsh peat bogs provide a unique historical environmental record since the last Ice Age.

- The accumulated peat laid down in a peatland provides an opportunity to examine the entire history of the ecosystem’s development from the plant remains laid down over thousands of years. The peat archive also stores a record of the surrounding landscape in the form of pollen grains blown onto the peatland surface and subsequently preserved in the peat. Using a combination of plant remains (macrofossils) and pollen (microfossils) it is possible to reconstruct pictures of past landscapes and climatic periods, in the case of UK peatlands as far back as 10,000 years.

- Peat bogs soak up water like a sponge and can help reduce flooding. Without an ability to retain water a bog would not exist. Lowland raised bogs receive all their water via rainfall and the degree of water logging dictates the type of vegetation that grows there. Where peatlands are damaged by drainage, afforestation or burning, this ability to store water is compromised.

- Healthy bogs store carbon from the atmosphere; damaged ones release it (contributing to climate change). Peat bog development in Wales and the UK typically began around 10,000 years ago. As peat bogs develop they accumulate carbon, which has been gathered from the atmosphere by living plants in as they photosynthesise and grow. When these plants die their semi-decayed remains are locked away in the peat under anaerobic, waterlogged conditions, limiting further decay and loss of carbon. Once stored in the waterlogged zone as peat, the carbon is locked up. As a result peat bogs now hold 30% of terrestrial carbon, and are one of the largest carbon stores on Earth!

Swansea University students have begun to unlock the mysteries held within Pyllau Cochion lowland raised bog near Brechfa. Peat began forming around 9900 years ago, and pollen reconstructions have been revealed information about the landscape changes over this period. Fire history has also been re-constructed and it is possible that evidence has been uncovered of ancient Mesolithic fires 8000 years ago. Pyllau Cochion bog will continue to act as a Carmarthenshire time machine, until all of the mysteries from the past have been uncovered!

Using peat as a ‘time-machine’

1. Assessing changes in wetness

- Changes in the colour of peat tell us about shifts from wet to dry periods in the past.

- The colour of peat reflects the height of the water table and the degree of peat decay.

- During wet conditions, the water table is higher and more peat accumulates because decay is slow. The peat preserved is lighter in colour.

- During dry conditions the water table is low, and less peat accumulates as decay is faster, forming peat that is darker in colour.

- This can be assessed visually or in the laboratory, using special techniques.

2. Macrofossils

- As peat accumulates each year, mosses, seeds, wood fragments, grasses and charcoal fragments are preserved within it. These are called macrofossils.

- Macrofossils tell us which plants were living on the bog surface or were blown in from the surrounding habitats at the time the peat accumulated and if the bog experienced any outbreaks of fire.

- By recording the macrofossil fragments at different depths we rebuild a history of vegetation changes.

3. Pollen grains

- Each different type of plant produces a distinct pollen grain.

- Microscopic pollen grains derive from plants growing either on the surface of the bog, or can be blown in by wind. These grains are captured and preserved within the peat.

- By using a microscope in the laboratory, scientists can count and identify the specific pollen grains and record changes throughout the peat record.

- This technique allows us to reconstruct a history of vegetation changes on the bog surface as well as the surrounding landscape.

How do we know how old peat is?

1. Radiocarbon dating

Every plant takes in carbon as it grows. Carbon has three components, Carbon-12, Carbon-13, and Carbon -14. Carbon-14 is radiocarbon, and although it is only found in small traces it is very special because it is unstable. This instability means that as soon as a plant or organism dies it begins to decay at a known rate. This means that the amount left in organic remains can be converted into an age. Macrofossil remains extracted from several depths in the peat can be dated via radiocarbon methods.

2. Volcanic ash

Volcanic ash deposits can act as time markers in peat bogs. When a volcano erupts tiny volcanic ash particles are dispersed across large distances by wind, and can fall onto the peat bog surface and become part of the record. Volcanoes produce ash with a unique chemical fingerprint that is exclusive to that eruption. By analysing the fingerprints of ash layers found within a peat core, and matching those back to the eruption, we can determine the age of that peat section.

Swansea University analysed a peat core from Pyllau Cochion bog. This diagram summarizes what they found, with the help of illustrations of what the bog looked like over the thousands of years it has been forming. Down the left-hand side of the diagram you can see the peat core - almost 8 m deep! This shows the grey silty clay deposits formed when the bog was a small lake, and shows how the lake bottom became more silty and eventually, over thousands of years, developed into a peat bog, becoming full of organic matter. The numbers in purple are the exact dates revealed by the radiocarbon dating.

Alongside the diagram there are photos of charcoal, plant fragments, pollen and small stones, all found in the peat core and illustrations of how the landscape will have looked at certain points in its history.

- Lowland raised bog is one of Western Europe’s rarest and most threatened habitats. The area of lowland raised bog in the UK has decreased by around 94% over the last two centuries from c 95,000 ha to c 6,000 ha at the present day. 800 ha of the lowland bogs that remain are within Wales. Much of it needs restoration to bring it back to its natural state.

- Many bogs have been drained and planted to make way for forestry or agriculture.

- Since the 1960s peat has been used to make compost, heavily used in commercial and amateur horticulture. This is mainly supplied from Scotland and Ireland with some imported as well.

- Bogs have also been damaged by drainage, pollution, burning and overgrazing.

- When peat bogs become degraded, the carbon stored within can be released back into the atmosphere, and this could have devastating impacts, by accelerating global warming.

- In a damaged bog the surface layer (acrotelm) has often been lost because of drainage, burning, trampling, grazing, atmospheric pollution, afforestation or even agricultural inputs such as fertilizer and seeding. This exposes the unprotected sub layer (catotelm) peat to the effects of oxygen, sun, wind, frost and rain and so it begins to degrade, losing carbon back into the atmosphere and into watercourses as it does so. The bog may still be covered with vegetation cover such as heather or rough grassland, but this vegetation is not adding fresh peat because it is not a wetland vegetation.

- Some countries still produce energy through peat-fired power stations.

Public engagement

One of the main objectives of the project was to show local people the bogs and demonstrate how the peat was surveyed and how prehistoric people would have used the sites. Visits to the bogs were arranged and a special event took place at the National Botanic Garden Wales where visitors spent the day finding more out about bogs and why they are important.

Research and management

Management has taken place to try and keep the bogs safe from arson and to block ditches that were allowing water to drain from the bog. Also Swansea University analysed a peat core to reveal the secrets over bog over thousands of years.

Planning

Planning Application Guide

- Development Idea

- Do I need a Planning Agent?

- Key Information

- Pre-Application Stage

- Types of Planning Application

- Application submission

- Validation

- Live Application

- Planning Committee

- Appeals

- Compliance / Enforcement

- Completion of Development

Major Planning Applications

Extending / changing your home

- Lawful Development Certificate

- Pre-application advice service

- Householder planning permission

- Neighbouring properties / party walls

- Bats and nesting birds

- Conservation areas

- Listed buildings

Search for a Planning Application

Breach of planning

Change of Use (Planning)

Pre-application consultation (PAC)

Highways planning liaison

Development Viability Model (DVM) Assessment Tool

Sustainable Drainage Systems (SuDS)

Apply for Section 106 funds

Local Development Order (LDO)

Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas

- Understanding listing

- When is listed building consent required?

- Alterations to Listed Buildings

- Applying for listed building consent

- What happens after a decision on listed building consent has been made?

- Works to a listed building without consent

- Maintenance and Repair

- Further sources of information

- Conservation Areas

Conservation & countryside

Street naming and numbering

My Nearest - Planning information

Planning Policy

- Local Development Plan 2006 - 2021

- LDP Review Report

- Supplementary Planning Guidance (SPG)

- Affordable Housing

- Affordable Housing areas

- Annual Monitoring Report (AMR)

- Housing Land Supply

- Community Infrastructure Levy (CIL)

Local Development Plan 2018 - 2033

- Integrated Sustainability Appraisal and Habitats Regulations Assessment

- Delivery Agreement

- Candidate Sites

- Inspector’s Report and Adoption

- Submission and Independent Examination

- Second Deposit Revised Local Development Plan

- Preferred Strategy (Pre-Deposit Public Consultation)

- Development of an evidence base

- Frequently asked questions

- First Deposit Revised LDP

Renewable Energy

Planning Ecology

New phosphates targets

- What action have we taken?

- West Wales Calculator

- Mitigation Measures

- Next Steps

- Phosphates - Frequently Asked Questions

- Teifi Demonstrator Catchment Project

Biodiversity

- Why biodiversity matters?

- Priority Species in Carmarthenshire

- Priority Habitats in Carmarthenshire

- Carmarthenshire Nature Partnership

- HLF Bogs project

- Marsh fritillary project

- Hedgerows

- Woodlands

- Pollinators

- Get out and about!

- Legislation and Guidance

- Protected sites

- Ash dieback disease

- Wildlife in your Ward

- Local Places for Nature

Waste

More from Planning